Four years ago, when reviewing Nigel Philip Davies’ first album, Songs from a River, I tried to put my finger on what it meant, culturally (pretentious, I know, but I can’t help myself). More as a result of desperation than inspiration, I invented a genre for it, Old Wave music, and opined that it reflected “the reality of the ageing of the boomer generation: the generation that invented youth culture, now coming to terms with its own mortality”.

Having just listened to the Welsh singer/songwriter’s second album, Reflections, I’m allowing myself to feel that I wasn’t so wide of the mark after all.

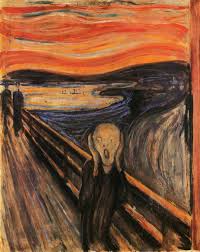

Nigel Philip Davies: a moment in time

In fact, this collection of songs inclines me to double down on my original assertion. The more you listen to it, it feels less like an album and more like a moment in time: a generation (mine/ours) looking back on its era and putting its emotional affairs in order in preparation for what we know we’re all going to face in the not too distant future.

Not that this is album is all doom and gloom—far from it—and I stress that this interpretation is very much my own, no doubt coloured by our current reality of coronavirus lockdowns, social unrest and rising geopolitical tensions. I don’t know if Davies would agree with my take on the album, and I’m not even sure that he had an over-arching theme in mind when putting it together. But the songs, while covering a variety of styles and themes, have certain elements in common that point (in my mind, at least) to a sense of cohesion.

These elements are an historical perspective—both in a formal sense (one of the highlights is a song about the holocaust) and a personal one (the passage of time and its effect on relationships)—and a lightly-worn awareness on Davies’s part of where he and his songs fit into the traditions of post-war popular music. It’s this combination of the themes of ephemerality and cultural exceptionalism which makes me think of this album as a sort of living epitaph for one of history’s most privileged, wayward and creative generations.

All of which probably means nothing more than that I’m feeling my age. So, what about the songs?

SONGS THAT RESONATE

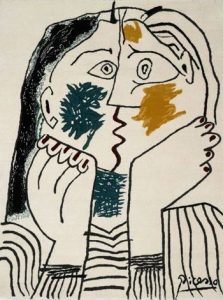

The opener, “I’ve Been to Berlin”, is one of two jazz-influenced numbers which are a throwback to a phase of Davies’ career that pre-dates his formation of (now dormant) folk-rock band Moongazer. The song celebrates Berlin’s glory as a bohemian metropolis but does so in a style reminiscent of the 1966 musical (and 1972 film) Cabaret, based on writer Christopher Isherwood’s pre-war experiences of the city. Whether or not the association is intentional, it does point up the fact that there’s a direct line of historical continuity between Berlin’s pre-war decadence and its post-modern edginess.

Liza Minelli in ‘Cabaret’

There’s a risk with this style of criticism (i.e. trying to see songs, albums etc. in a cultural/historical context) of reading too much into things. Having made that caveat, I’m now going to say that, for me, the song traces a perfect historical arc for both the baby-boomer generation and Berlin itself: the boomers, born out of the rubble of World War II, came of age in the late 1960s when Berlin, rebuilt on the ruins of Hitler’s bunker, began to experience a cultural renaissance (the contemporary-music component of which, for example, was led by Tangerine Dream, formed there in 1967). When a boomer writes a song about today’s Berlin, and does so in a way that evokes the city in the 1930s and 1940s, such inferences are hard to resist.

So the opening track, whether by accident or design, anchors the listener’s expectations in historical and cultural references that can resonate fairly strongly with the post-war generation.

“I Live Alone” reverts to Davies’ more familiar folk style with some nicely picked acoustic backed by ambient strings and piano, its melancholy standing in marked contrast to the man-of-the-world bravura of the first track. The theme is love and loss, but something else too: “I live alone with this heart of stone, since I laid down this traitor’s throne…for my sins I must atone.” There’s a sense of emotional and moral exhaustion, an old order giving way, self-doubt, guilt and an uneasy reckoning with destiny. Not the sort of song you want to listen to last thing before going to bed, unless you’re a very sound sleeper not given to pangs of conscience.

The title of the next track, “Good Times”, immediately brings to mind the 1967 song of the same name by The Animals and there are similarities, especially the idea of a pub sing-along chorus (the British beat band placed theirs in the middle of their song while Davies uses his as the outro). While The Animals’ number has a regretful tone (young man laments his life of sinning when he could have been winning etc.), Davies’ is a more positive exercise in nostalgia, the sense of lost youth redeemed, to some extent, by the power of memory to make far-away and long-ago friends seem present here and now. The song is carried along by electric piano but solos from a surging Hammond-style organ and distorted electric guitar—Davies plays everything—add a keen edge.

Dylan is the next musical influence to get a nod, on “A Lifetime Ago (Or Maybe Two)” and “Better in the Morning”, both of which feature the master’s tinny, dissonant harmonica style and some of his vocal phrasing and lyrical feel. In “Lifetime” the hommage is secondary to the sense of Davies’ own life experience, captured vividly in the opening lines: “A lifetime ago or maybe two, the first time I set eyes on you,/pushing through the party crowd, head held high and oh so proud;/ I was laid out in a daze but through the haze I felt amazed by you.” This sets the scene nicely for a tale about socially mismatched love (“Lady and the tramp, they said—you so slim, me just underfed”) but the song ends in something of an anti-climax as the relationship’s (inevitable) failure is dealt with in a vague and almost offhand way.

The great man is more to the fore in “Better in the Morning”—a phrase, according to the album notes, often used by Davies’ mother when he was young to encourage him to take a more optimistic view of life. It didn’t work, judging by the ironic contrast between the title and the song’s dystopian social commentary: “The rich are getting richer as the huddled mass looks on/and dances in tiny circles to a politician’s song,/and every step is choreographed from the selection box of life,/while in a cold apartment another valued voter dies,/another hopeless, hapless martyr to the god of free enterprise.” The song has all the characteristic bite of Davies’ satirical pieces but, in the final analysis, it struggles to rise above the depressing realisation that, since Dylan brought the protest genre to perfection in the 1960s, things haven’t changed much; indeed, they’re probably worse.

“Always on Your Side” is a more personal form of self-expression, with Davies himself rather than his influences centre-stage. This is a moving song about lost love and well executed: the emotion in Davies’ voice is complemented by the intimate vocal ambience achieved by the mix, and the instruments—two acoustic guitars, bass, synth strings and piano—work together seamlessly. He’s a deft lyricist, too. The last line of the chorus, the first couple of times he sings it, is: “If you know how hard I tried to save you from the pain that comes when two worlds collide.” The final time he sings it, “collide” is replaced by “divide”. It packs a subtle, but effective, emotional punch.

At first listen, “Won’t You Be Mine,” is pure throw-away pop: the upbeat tone and annoyingly infectious hooks recall the bubble gum music targeted at pre-teens during the late 1960s (“Mony Mony” by Tommy James and The Shondells and “Sugar Sugar” by The Archies spring immediately to mind). Hell, the lyrics even include the phrase, “I wanna be your man”! It seems to be nothing more than a sugar-coated invitation to have sex, but there’s more going on beneath the surface. In fact, Davies turns the subgenre on its head, replacing the sense of optimistic young love with a poignant awareness of mortality: “Life passes by in the blink of an eye, look away and your dreams fall behind…Life is a game that we won’t play again”. The goofy synth solo completes the inversion. It’s as though Davies travels back in time, abducts the musically formative years of a generation, then brings them back to the present, condensed into four minutes and 20 seconds of satire, irony, and sobering reality.

“1941” is the holocaust song referred to earlier. This, say the album notes, was part of a 27-minute magnum opus Davies performed with another pre-Moongazer project, prog-rock band The Vacant Chair. It would be interesting to hear the full cut, as the monumental theme and stadium-rock cadence of the chorus seem well-suited to a large-scale production. But this stripped-down version works well. The lyrics are a little stiff and formal as if, like pall bearers, they are conscious of the weight they bear, but they stay this side of bathos. Much of their emotional power comes from the way that the meaning of the chorus—“I’m still standing”—changes over the course of the song. When the first verse refers to the loading of the trains and the “flame of hope” being extinguished, the chorus sounds like survivor guilt; when the last verse alludes to the flame being rekindled by the fight for freedom, the chorus becomes a forceful testament of witness and memory.

“True to Yourself” is another strong track which sounds as though it would go down well with a big, live audience, based on the emotional warmth of the piano and synth cello arrangement, the rising chord progression and the lyrics’ potential to inspire. It strays a bit close at times to the kind of motivational messaging that pops up in your Facebook feed every day, but it has a big heart in the right place. One can imagine Davies singing it to his kids (and grandkids, too!) and, in the context of this album, there’s an engaging pathos in the idea of an older generation singing to a younger one. It’s basically Davies doing what his mother did when she told him that it would be “Better in The Morning”. What goes around comes around.

“Why Don’t You (Close Your Eyes When We Kiss)” takes us back to the relationships theme and the sinking feeling that the one you love no longer loves you. The song lands easily on the ear with a light, wistful melody and simple, understated lyrics. The simplicity is deceptive, however, as the overall impression—helped by the sparse, chiming instrumentation of piano and acoustic guitars—is that the song is as delicate and fragile as the relationship it describes. There’s also an unexpected chord change between the verse and the chorus which, while musically pleasant, leaves you feeling slightly off balance and conveys perfectly the singer-protagonist’s own mood and perspective.

Davies’s jazz past resurfaces in “Smile”, a jaunty singalong driven by piano and a nicely tripping (in the light-fantastic sense) bass which might be guitar or synth but sounds just like double bass (you can almost see the armbands and silk waistcoat).

This is meant to be a pick-you-up-when-you’re-feeling-down number, like the song of the same name first recorded by Nat King Cole in 1954 (based on a tune written by Charlie Chaplin for his 1936 movie Modern Times) and covered by innumerable others since. Coles’ song (and the scenes in Chaplin’s film that the music sound-tracked) offered an antidote to the general vicissitudes of life; Davies’ song, however, is about growing old—“The tide of doubt is rising, you think you’ve had your day, all the tunes you used to love now no-one seems to play…”—and is another example of what I consider to be the album’s demise-of-the-baby-boomer theme. (The song also echoes, in wit and spirit, “Look on the Bright Side of Life” from Monty Python’s Life of Brian movie—a more ‘boomerish’ cultural reference than Cole.)

And so to the final track, “Going Home”, a folk song in the “Wild Rover” tradition but more melancholic and reflective. It’s the perfect sign-off for this album, looking back on a full but not entirely satisfactory life and turning towards a horizon where home is not some romantic illusion or escape (no “green, green grass” here) but something more final, symbolized by the “western skies”. It’s been a long road and, as so often happens, the journey has turned out to be the destination: “I have sought salvation in a thousand bars where all men look the same and everyone is a friend of mine, no one knows my name…/ All the things I looked for, I thought would set me free, they were there the whole time through, lost inside of me.”

The song ends quietly, quickly, with no fuss, leaving the silence to echo in the listener’s mind.

PROUD IN THE INDIE TRADITION

Like its predecessor, this album stands proud in the DIY indie-music tradition. Its modest production values give the sound a raw edge which add to the sense, reflected in each song, of a man responding as honestly as he can to the curve-balls that life throws at him (and, by extension, us). In many other comparable recording artists, these factors might be limitations, but that’s not the case with Davies, whose range of interests as a songwriter and skills as a musician combine to make this album much, much more than the sum of its parts.