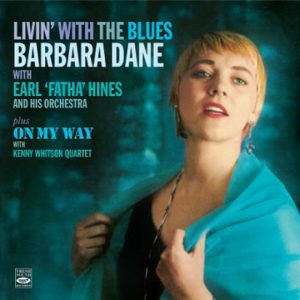

Two blues tracks—one New Orleans jazz-style, the other a hard-edged post-Chicago blues-rock sound—recorded 57 years apart. They’re the same song. One other thing they have in common: the singer.

Barbara Dane, ladies and gentlemen.

If you haven’t heard of her it’s probably because you grew up in the 1960s or later and you’ve been too busy listening to all the people—Bob Dylan and Bonnie Raitt are just two off the top of my head—who have been influenced by her extraordinary career of singing and activism.

At 92, she’s still with us, thank God, and still performing on special occasions. Let that sink in: born in 1927 and still singing the blues.

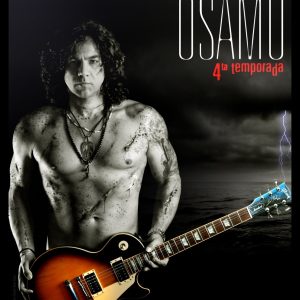

And how. Here’s her most recent recording of “Good Morning Blues”, with Cuban rocker Osamu Menendez and his band.

That was cut in 2014, when Barbara was 87. This is her first-ever recording of the song, with the sublime clarinettist George Lewis, in 1957:

“I sound so green I can hardly recognize myself,” Barbara says now of that earlier recording. You can see her point, but it’s not just the 57-year difference in her voice, it’s the contrast in the styles of music too.

In the George Lewis version, the music has the classic demeanour of an old bluesman, dogged and sweetly melancholic, while Barbara’s voice is strong and soulful in a wholesome way which, while sympathetic to the music, provides a contrasting sense of freshness.

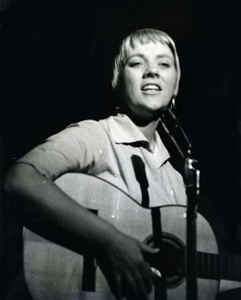

Barbara then…

But it’s not “green” in the sense that most people would use the word. It’s the voice of the “good gal feeling bad”, trying to hold everything (including her relationship with a cheating man) together through sheer strength of will and personality, with little hope and even less romantic illusion.

Wind the clock forward and we’re almost in post-apocalyptic territory, musically and visually. The overtly political video was posted—and presumably created—in 2017, three years after the audio was recorded. Timewise, they chart an arc that starts a year or so after the launch of the Black Lives Matter movement and ends the year that Trump came to power.

Put the video to one side for a moment, and just listen to the music. Osamu’s arrangement draws heavily on the old Lil’ Son Jackson/Muddy Waters “Rock Me” riff (that’s the sexually menacing one, not to be confused with B.B. King’s much silkier “Rock Me Baby”) and the band—led by Osamu’s seething guitar and a harmonica that howls like a junkyard dog—locks it down tight.

What’s surprising is how well Barbara’s voice—weathered and leathery at the edges, but still rich and gorgeous at the centre—suits the treatment. It’s far more at home in this dystopian soundscape than the voice of her 30-year-old self could ever be.

…and now

How can a 92-year-old singer, with a career behind her that’s longer than most people’s lives, be so bang-on relevant today? Has Barbara evolved with the times, or have the times finally caught up with her? I suspect that the answer, if there is one, lies somewhere in her backstory.

AN INTERESTING TENSION

Barbara, first and foremost, has always been her own woman—one blessed with an outstanding voice and a passion for social justice. According to that fount of all knowledge, Wikipedia, “Out of high school, Dane began to sing regularly at demonstrations for racial equality and economic justice. While still in her teens, she sat in with bands around town and won the interest of local music promoters. She got an offer to tour with Alvino Rey’s band, but she turned it down in favour of singing at factory gates and in union halls.”

As that last sentence suggests, music and social justice have always been two sides of the same coin for Barbara. Her career as an activist has included travelling to Cuba in 1966 as the first US musician to tour there after Castro’s revolution, leading (while playing guitar and singing) civil rights marches and protests against the Vietnam war, touring and performing for anti-war GIs, campaigning for the environment and joining Pete Seeger in New York in 1978 in support of a miners’ strike.

In 1964, Bob Dylan wrote, in a letter to Broadside magazine, “The world needs more people like Barbara, someone who is willing to follow her conscience. She is, if the term must be used, a hero.”

Dylan sits in with Barbara at a gig in 1963

In terms of her social activism, then, Barbara has been a leader and an agent of change, someone ahead of her times. There was, and continues to be, a natural affinity between her political views and the music she loves and plays, which is essentially the music of the underdog. But there’s an interesting tension in the fact that while Barbara is a political progressive she is, musically, steeped in tradition.

How does that tension resolve or contain itself? It comes back, I think, to the fact that Barbara is her own woman, artistically as well as politically. She is equally at home in, as well as adept in, folk, jazz and blues. Her musical achievements are the stuff of legend but all I can do here is list, in no particular order, some (and only some) of the people she’s played with: Memphis Slim, Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Clara Ward, Mama Yancey, Little Brother Montgomery, Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, Art Hodes, Roosevelt Sykes, Otis Spann, Willie Dixon and Wilbur De Paris (Wikipedia). Not listed by Wikipedia, but two of my favourites, are Lightnin’ Hopkins and the Chambers Brothers.

Lightnin’ and Barbara

In 1961, she gave a uniquely personal expression to her commitment to music and social justice when she opened her own club in San Francisco to introduce the blues to a wider, white audience. In 1970 she founded her own record label to promote international protest music.

Her musical originality works in the same direction as her political singlemindedness: the fact that she sings beautifully and authentically across genres makes her, within her field, diverse and unclassifiable; her ability to reveal the universal spirituality that lies so deep in jazz and blues transcends the music’s racial origins (she was one of the first white female artists to be profiled by Ebony magazine[1]), and her selfless promotion of other artists created new audiences and new possibilities. In her music—particularly in the way she has interpreted and promoted it—she has always been ahead of her times.

In what sense, if any, has she evolved with them?

YES AND YES

Earlier, I contrasted the progressiveness of Barbara’s politics with the traditionalism of her music. I confess to being a little disingenuous there, as I implicitly associated the politics with some sort of dynamic quality and the music with a more static one. But, as we all know, traditions must live, breathe and change if they are to survive. It’s in that sense that I understand Barbara to have evolved, and I can’t think of a better way of illustrating what I mean than by going back to “Good Morning Blues”—both the history of the song, or part of the history, and her two versions.

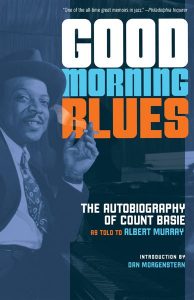

His Excellency

Count Basie is credited as the composer and his recording of it was issued in 1937, when Barbara was 10 (yes, I know it’s rude to harp on about a lady’s age but, hell, this is history). The lyrics, sung by Jimmy Rushing, were, one might say, a little on the light and frothy side:

Good morning blues, blues how do you do

Good morning blues, blues how do you do

Babe, I feel alright but I come to worry you

Baby, it’s Christmas time and I want to see Santa Claus

Baby, it’s Christmas time and I want to see Santa Claus

Don’t show me my pretty baby, I’ll break all of the laws

Santa Claus, Santa Claus, listen to my plea

Santa Claus, Santa Claus, listen to my plea

The next version I’ve come across was by Lead Belly, recorded in 1940 when Barbara was… nah, you work it out.

Lead Belly: bluesman and convicted killer

Now the song gets serious (the lines in italics are spoken):

Now this is the blues

There was a white man had the blues

Thought it was nothing to worry about

Now you lay down at night

You roll from one side of the bed to the other all

Night long

Ya can’t sleep, whats the matter; the blues has gotcha

Ya get up you sit on the side of the bed in the mornin’

May have a sister a mother a brother n a father around

But you don’t want no talk out of em

Whats the matter; the blues has gotcha

When you go in put your feet under the table look down

At ya plate got everything you wanna eat

But ya shake ya head you get up you say “Lord I can’t

Eat I can’t sleep whats the matter”

The blues gotcha

Why not talk to ya

Tell what you gotta tell it

Well, good morning blues, blues how do you do

Well, good morning blues, blues how do you do

I couldn’t sleep last night, I was turning from side to side

Oh Lord, I was turning from side to side

I wasn’t sad, I was just dissatisfied.

I couldn’t sleep last night, you know the blues walking

‘Round my bed,

Oh Lord, the blues walking ’round my bed

I went to eat my breakfast, the blues was in my bread.

Well good morning blues, blues how do you do.

Well, good morning blues, blues how do you do.

I’m doing all right, well, good morning how are you.

The blues evoked by Lead Belly are dark and sinister, in the tradition of Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound on My Trail”. Barbara, in her version with George Lewis, drinks from the same well, but with a difference:

Oh, good morning blues, blues how do you do

Oh, good morning blues, blues how do you do

Oh, I’m feeling mighty well baby how are you

I got up this morning the blues walking round my bed

I couldn’t sleep I got up this morning the blues walking round my bed

I went to eat my breakfast the blues was all in my bread

The blues ain’t nothing but a good girl feeling bad

The blues ain’t nothing but a good girl feeling bad

I lost my good man and every dime I ever had

I’m going down to the river and sit down on a log

Oh I’m going down to the river and sit down on a log

If I can’t be your woman I’m not gonna be your dog

I sent for you yesterday but you come walking today (24 hours late)

I sent for you yesterday but here you come walking today

Well, If you can’t do no better why don’t you just stay away, stay away.

By introducing the line, “The blues ain’t nothing but a good girl feeling bad,” Barbara manages to be traditional and innovative at the same time. It’s based on what is probably one of the most famous lines in blues music—“The blues ain’t nothing but a good man feeling bad”—from one of the first blues songs ever published, in 1912 (in a way which, by today’s standards, would be spectacularly politically incorrect). But, just as Barbara takes “Good Morning Blues” back to the origins of its genre, she updates the song by re-gendering it. She breaks with Basie and Lead Belly and makes it something new—a woman’s song. Her artistic initiative in this respect is distinctive and personal, but what she creates is historically significant for all women.

True, Barbara wouldn’t have been the first female blues singer to feminise a song, but “being first” isn’t the point. The re-gendering of songs is a tradition within the broader blues tradition, and Barbara makes an original—in the sense of distinctive and personally authentic—contribution to both. I’m familiar with only two other versions of “Good Morning Blues” by female singers, both of which post-date Barbara’s: Ella Fitzgerald’s (1960) and Della Reece’s (1999). Both are a world (in Fitzgerald’s case, a universe) away from Barbara’s sassy feminism.

The point seems to be that, even when she breaks new ground, Barbara affirms the tradition within which she works.

In Japan, the name means “discipline, study”

Here are the lyrics of her version with Osamu:

Well, good morning blues, blues, blues how do you do

Good morning blues, blues, blues how do you do (looking pretty good)

Oh, I’m feeling mighty well but I want to know how good, partner, are you?

Let me say what happened to me last night

I lay down last night I was rolling from side to side

I lay down last night I was rolling from side to side

Do you know what, I was not sick honey I was just dissatisfied (you know what I’m talking about)

Well I rolled and I tumbled and cried the whole night long

Well I rolled and I cried, cried the whole night long

Now I had the blues so bad, I couldn’t tell right from wrong

Well I sent for you yesterday and you come walking today

You dragging them dogs and you come walking today

If you can’t do no better I’m going to throw your old number away

I’m going down to the river and sit down on a log

Oh I’m going down to the river and sit down on a log

If I can’t be your woman I’m not gonna be your dog

The delivery of these lines is certainly more knowing, and humorously so, than on the “green” 1957 version (incidentally, humour is very much part of Barbara’s style; check out “The Kugelsburg Bank” on her Throw It Away album—it’s hilarious). But, while Osamu’s urban rock places this interpretation by Barbara firmly in the early 21st century, Barbara draws once again from the early history of the blues by including lines (my italics) from “Rollin’ and Tumblin’”, first recorded in 1929, by Hambone Willie Newbern. It’s probably one of the most-recorded blues songs of all time (I first heard it on Big Joe Williams’ Classic Delta Blues album, released in 1964).

So, in answer to the question, “Has Barbara evolved with the times, or have the times finally caught up with her?”, the answer appears to be “Yes, and yes”. She’s as relevant today as she has always been because—by virtue of her fierce independence, originality and musical gifts—she has placed herself both at the leading edge of social change and at the living core of a self-replenishing tradition, the two—change and tradition—working together seamlessly.

Everything about this pic says “iconic”

From this perspective, I would argue that Barbara’s long life and career are best seen, not in terms of simple linear progression, but more as a continuous backtracking and moving forward, the effect of which has been to broaden and deepen her art and political commitment constantly, to the spiritual enrichment and benefit of her audience and, from all accounts, those who have known and worked with her.

It’s quite a legacy, but that’s not all. A documentary about Barbara’s life is under way: true to Barbara’s principles, this is not a slick Hollywood production but relies mainly on donations, which you can make here. Better still, Barbara’s legacy won’t be confined to video, or audio, or the written word. It’s already alive and kicking in the next generation of impassioned musicians: Osamu is her grandson….

Music dynasty: Barbara, son Pablo and Osamu

[1] Downbeat.com