Australia Day means different things to different people: for Anglo Australians, it marks the beginning of European settlement and the transformation of a pristine wilderness into a modern democratic nation state; for many indigenous Australians, it’s “Invasion Day”, the beginning of the end of their traditional way of life and the source of their present-day difficulties.

In my case it was the date in 1991 when, with my pregnant wife and young family, I left the UK to make our home here.

After a 24-hour flight and the adjustment of our watches, we arrived on January 28 to find that the area of Sydney where we were to spend our first few weeks had been devastated by a cyclone. Just two weeks later my wife went into premature labour. She was hospitalised. The baby – the longed-for sister for our two sons – was born two months later but survived only a few hours.

Welcome to Australia. Source: The Daily Telegraph

Our personal history has much in common with that of other migrants and, indeed, the history of modern Australia: a fresh start, hope, crushing disappointment, resilience and survival. We have our third child: he’s a fine, strapping young man, just like his elder siblings. Not only that, but we have just welcomed our first grandchild (another boy!) into the world. Life doesn’t get much better.

So, when I think of Australia Day, I think of a lot of things, good and bad.

Consequently, it’s not hard for me to imagine that Australia Day is good for some people, less good for others. I’m not a fan of the black arm-band view of history and I love this country unreservedly, but I’m not blind to its faults. I have no first-hand experience of the kind of deprivation suffered by many indigenous Australians, but I’ve seen enough of it to know that it’s real and to understand why Australia Day is alienating for many of our first people.

So, let’s change the date; and let’s not.

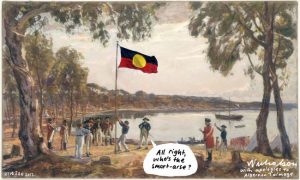

Peter Nicholson, The Australian

I’m conciliatory rather than combative by nature, and the heated – and, all too often, overheated – debate about whether to change the date and what the new date should be doesn’t float my boat. So much of it is little more than grandstanding; no-one appears to be seriously committed to finding a solution. For what it’s worth, here’s my suggestion.

In the interests of acknowledging our history, both the good bits and the bad, and celebrating our achievements, let’s keep Australia Day on January 26. And let’s choose an entirely different day as “New Australia Day”.

That’s right – two Australia Days, if you like, each with a different but complementary purpose. While January 26 would still look at our past, and at our present in the context of that past, New Australia Day would challenge us to look to the future as one people. While January 26 would still celebrate what we have been and what we have become, New Australia Day should inspire us to embrace our potential to become something bigger and better – more egalitarian, more inclusive, more open-minded and open-hearted…more Australian, in the best sense.

Naturally, only one of these days would be a public holiday, and I think it should be New Australia Day. The change would be an acknowledgement that Australia has moved beyond (but not forgotten) its British and European roots and is maturing as a multi-cultural society which values its shared traditions, including those of indigenous people, and the opportunity they represent to create a richer and fairer future for everyone.

Mark Kenny recently argued in the Sydney Morning Herald for changing Australia Day to May 9. His reasons for choosing that date were good, but I think it would be a better New Australia Day.

C’mon Aussies, let’s end this pointless bickering and meet each other halfway with a double-barrelled national celebration which, while admittedly a compromise, is still symbolically meaningful: an acceptance of our past together on one day, followed at a later date by a new imaginative space in our national life in which we can come together and pool our strength, hopes and visions for the future.