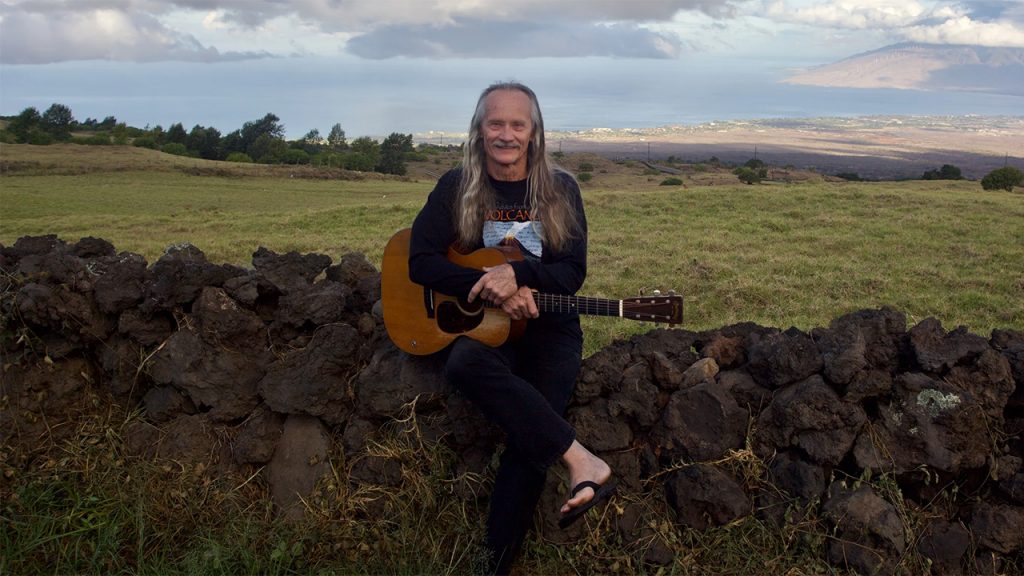

Smiling, tanned, relaxed, sitting in a studio on his island home of Maui in the Hawaiian archipelago, Jeff Cotton is a very different man from the one who, 52 years ago and physically and mentally close to breaking point, finally quit what had been his dream job.

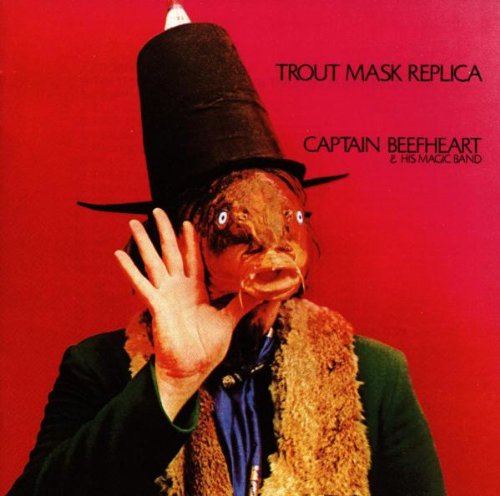

Jeff, then known as Antennae Jimmy Semens, had been one of the two guitarists with Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band, a legendary US ensemble that made an equally legendary album, Trout Mask Replica. Released in 1969, the album continues to be both controversial and influential.

Artists are supposed to suffer for their art, but not the way Jeff had done.

“Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band was my Vietnam,” he says.

Shortly after joining the band in 1967, Jeff received his call-up papers to serve in the Vietnam War.

“Obviously, I didn’t want to go to another country and take out my brothers and sisters, of any age, whether the children or elderly. The band wanted me and I wanted to be in the band, so, we did everything we could to get me out [of the draft], and we did get me out.”

Before long, however, Jeff found himself in the midst of another conflict. Beefheart, real name Don Van Vliet, was a creative visionary but, to put it mildly, a hard task master.

The band shared a house. While they typically rehearsed 18 hours a day for the Trout Mask Replica recording session, Beefheart usually slept. When he appeared, it was often to subject Jeff and the others to verbal and mental abuse, apparently to bend them more easily to his creative will.

Beefheart even encouraged violence. When Jeff was physically attacked by a stand-in drummer, he decided enough was enough.

“I thought I could escape war in Vietnam, but if that [war] is what’s laid out in front of you, you’re going to have it anyway. So, I had my Vietnam in the Magic Band. It was probably, for me, as intense and emotionally wrenching as going to war.”

His acceptance that war of one kind or another was to be his lot says much about Jeff’s philosophical take on life. It’s an attitude deeply embedded in his first solo album, The Fantasy of Reality, which he is about to release (August 12, 2022) to mark his return to the music scene after a 47-year absence.

The new album is a long way from Trout Mask Replica.

SMALL SIMILARITIES, BIG DIFFERENCE

Except, that is, in a couple of minor respects.

I suggest that his vocal on Elvirus is reminiscent of Beefheart. It’s a stretch, I know: Jeff’s light quavering tenor is nothing like the Captain’s booming baritone, but the falsetto flick-ups that punctuate much of his intonation echo a hallmark of Beefheart’s style.

Jeff disavows any mimicry.

“Every song I write tells me what it needs in voice or whatever. I’m 74, and I think I sound more like 97. But I like humour. On Heavy, another song on the album, I use a very old man’s voice. I won’t tell you who he was but I used his voice.”

But Jeff does see a link between Trout Mask Replica and one of his instrumental tracks, On the Thread.

“That’s one of my favourites because I do like avant-garde-type music. And Beefheart fans may not see it exactly as I do. They may say, ‘Well, that doesn’t seem too Beefheart to me,’ but that’s my concept. Had I been more influential back then in the Trout Mask days, the songs would have probably been a little more conservative, like On the Thread.”

Of the three instrumentals on Trout Mask Replica, the one likeliest to offer a line of descent to On the Thread (to my ears, at least) is Hair Pie: Bake 2. Both tracks have a full band arrangement (Jeff played all the instruments on The Fantasy of Reality, and programmed the drums) and foreground intricate interplay between guitar parts.

But there the similarity ends. While Hair Pie: Bake 2, like the rest of Trout Mask Replica, is harsh and discordant, On the Thread is light and airy—indeed, almost airborne.

The difference provides clues not only to where Jeff stands, musically and personally, in relation to Trout Mask Replica, but also to his innermost character, and to the distance he has travelled, emotionally and philosophically, since, as a 21-year-old, he helped make that iconic album.

FROM FRAGMENTATION TO WHOLENESS

This article is not meant to be about Trout Mask Replica. The album casts a long shadow, however, and it seems necessary to enter the darkness to draw Jeff and his own album into the light.

While Trout Mask Replica has grown in critical esteem over the years, it continues to divide ordinary music fans into lovers and haters. Prior to its release, Beefheart and the various incarnations of the Magic Band had been a respected blues-rock outfit with increasingly psychedelic leanings.

With Trout Mask Replica, they shredded that legacy. Steady beats were abandoned in favour of arhythmicality and clashing time signatures, while melody and harmony gave way to atonality and a sonic grind based on random horn-blowing, strangulated guitars and Beefheart’s wild vocals.

Even fans would concede that it sounds like a bear roaring drunkenly to the accompaniment of metal scraping against metal. But they hear something else, too: an underlying order and beauty.

Beneath the chaos, many elements and influences are at work, from the band’s roots in the delta blues to the free jazz of John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, and even (according to those who know about these things) the serialism of Stockhausen and fragmentariness of Stravinsky.

At the risk of sounding pretentious (oh, go on, then), it reminds me of T. S. Eliot’s classic modernist poem, The Waste Land. Both break down accepted artistic forms. In the poem, Eliot uses the phrase, “a heap of broken images”. It could easily describe both the poem and the album.

The Fantasy of Reality couldn’t be more different. Instead of fragments it offers an aesthetic wholeness based on Jeff’s rich blues sensibility and deep spirituality—both of which are evident on the album’s opening track, Does It Work for You?

What, in Jeff’s view, does the album say about how he has developed, musically and personally, in the last 50 or so years?

“40, 50 years ago, I believed in art for art’s sake and, today, I’m not interested in that at all. I’m interested in communication and connection with another being, another human being. So, all the music has evolved. The lyrics have evolved, and the music has evolved, in that direction.”

He cites as example another instrumental from the new album, a classically-flavoured solo-guitar piece called Ivy. Like On the Thread, it’s warm and lyrical, but takes its strength from a deliberate sparseness.

“I’m looking for the least notes, the simplest construct possible. You’ve heard it many times: It’s not what you play; it’s what you don’t play. It’s the silence between. That’s why I love music even more than film, in some ways, because music allows the listener to cocreate.

“And if there’s more space in the song, there’s more time and space for people to cocreate.”

For Jeff, the ideas of communication and cocreation have a philosophical as well as a musical dimension, because they are ways of drawing people closer to each other.

“We’re at a unique time in history. There’s never been anything like it before, and we’re all in it together.”

THE DROUGHT BREAKS

It was when he co-founded MU in 1971 with two old friends and musical collaborators, guitarist Merell Frankhauser and drummer Randy Wimer, that Jeff fully began to step out of Beefheart’s shadow.

MU—short for Lemuria, the mythical lost Pacific Ocean continent that preceded Atlantis—recaptured some of the idealism and optimism of the pre-Manson 1960s. The band’s fascination with the legend behind its name led to its relocation from California to Hawaii, now Jeff’s main home base.

It was around this time that Jeff began the healing process he alluded to in his YouTube interview a few years ago with Canadian musicologist Samuel Andreyev. It wasn’t just his time with Beefheart that he was healing from, however.

“By the time we’re teenagers, we have had a lot of reprogramming done on us. Unconscious reprogramming is a nice way to put it—or the dark side—where we don’t even question things until a certain time in our life. Maybe something will happen that’s really heavy and we begin to question our lives. Or some people say they hit a bottom before they started coming up.

“So, I had everything everybody else did to deal with as a kid, the emotional stuff.”

His time with Beefheart provided an extra difficulty, but he bears no grudges.

“I can look back at it and really enjoy it because, yes, I did a lot of healing work. I mean, right from the get-go—every kind of cutting-edge modality I could find. Rapid eye technology is outrageous. There are so many other different things that [I] did. And so, I cleared it, as much as I could.

“To me, it was important to clear the emotional garbage, because I don’t care how spiritual one may be, if one’s emotional body is polluted, all you’re going to do is shine that beautiful light through a maze of yucky colours. So that, to me, was a responsibility.”

In 1974 he converted to Christianity (but did not, contrary to some online bios, study for the Christian ministry). MU disbanded in 1975 after which Jeff devoted himself to family (he has three adult children) and medical missionary work. His wife Len-Erna—“a great musician and a wonderful writer”, with whom he co-wrote and performed at small, private gigs—died in 2017.

Since then, Jeff has been musically silent. But that’s all about to change. Not only is he releasing his first solo album, work on a second and third album is “70 to 80 per cent complete”.

It’s been a long drought. Why is it breaking now?

LET’S GET THIS FIRE LIT

There are two explanations for the timing. Technology is one.

“I didn’t get into recording music until about 2005, because I was always a little queasy about digital recording back in those days. To me, it was like a hospital—very clean and no character. When a console that was warm came on the market, I started recording.”

Raising three kids is another.

“A lot of the basic tracks on this first album were done in very little increments. If I had 15 minutes, I’d go down in the studio and lay down a part. Maybe a couple of hours later, I could come down for a half hour. After everybody went to sleep at night, I might be able to do two hours. So it was literally put together in that fashion.

And what about the motivation for making the album? Was Jeff driven by a desire to meet specific creative goals, or was the impetus deeper and more personal?

“It was deeper and more personal. I have wanted, all my life, to do something that counted for others. Not so I would just have a notch on my gun, but to do something for others that was positive. And that’s been my whole motivation. Now obviously, that’s a thought of a young kid, but as you get older, it takes on a deeper meaning.

“And we need love in this world. We need to love one another, is what we need now. We know that. And we need to do it because every human being on this planet is a genius. Many just don’t know it yet and they don’t know what their genius is.

“And so, my heart is to, hopefully—because I’m trying to live that life—inspire others to be motivated and then to begin their path and journey, if they haven’t already, to know who they really are, because everybody has a great magic within them.

“And if people get their fire lit, we can clear this world up.”